I’ve just finished Ben Horowitz’s brilliant book The Hard Thing About Hard Things – in which he shares his own widsom gleaned from being CEO of a start-up (Opsware) that was inches away from liquidation and ultimately went on to become very successful.

I’ve just finished Ben Horowitz’s brilliant book The Hard Thing About Hard Things – in which he shares his own widsom gleaned from being CEO of a start-up (Opsware) that was inches away from liquidation and ultimately went on to become very successful.

There’s no grandstanding in the book – Horowitz openly admits when he got things wrong, how he’d change things if he did them again and lifts the lid on some of the stuff most employees never give a second thought to when they do their regular hours.

Make sure you use those 1-2-1s effectively

Horowitz is particularly interesting on company culture, how important it is and why it’s way more than allowing people to play table tennis and use scooters to get around the office.

He talks very passionately about the regular catch-ups managers have with direct reports and why they’re so important for employees.

The key to a good one-on-one meeting is the understanding that it is the employee’s meeting rather than the manager’s meeting… During the meeting, since it’s the employee’s meeting, the manager should do 10 percent of the talking and 90 percent of the listening. Note that this is the opposite of most one-on-ones.

Many managers treat catch-ups as a way of imparting information that they could easily deliver via email, or a casual conversation at a desk.

Horowitz also suggests questions for managers to use, in order to get their staff to open up a bit and get proper feedback.

- If we could improve in any way, how would we do it?

- What’s the number-one problem with our organization? Why?

- What’s not fun about working here?

- Who is really kicking ass in the company?

- Whom do you admire?

- If you were me, what changes would you make?

- What don’t you like about the product?

- What’s the biggest opportunity that we’re missing out on?

- What are we not doing that we should be doing?

- Are you happy working here?

Why managers should treat 1-2-1s with reverence

But for any managers who think that absolves them of responsibility, Horowitz also has something to say.

It came to my attention that one of my managers hadn’t had a one-on-one meeting with any of his employees in more than six months.

Why did I demand that managers have one-on-ones with employees? After much deliberation with myself, I settled on an articulation of the core reason and I called up the offending manager’s boss and told him that I needed to see him right away.

When Steve came into my office I asked him a question: “Steve, do you know why I came to work today?… Why did I bother waking up? Why did I bother coming in? If it was about the money, couldn’t I sell the company tomorrow and have more money than I ever wanted? I don’t want to be famous, in fact just the opposite.”

Steve: “I guess.”

Me: “Well, then why did I come to work?”

Steve: “I don’t know.”

Me: “Well, let me explain. I came to work because it’s personally very important to me that Opsware be a good company. It’s important to me that the people who spend twelve to sixteen hours a day here, which is most of their waking life, have a good life. It’s why I come to work.”

Steve: “Okay.”

Me: “Do you know the difference between a good place to work and a bad place to work?”

Steve: “Umm, I think so.” …

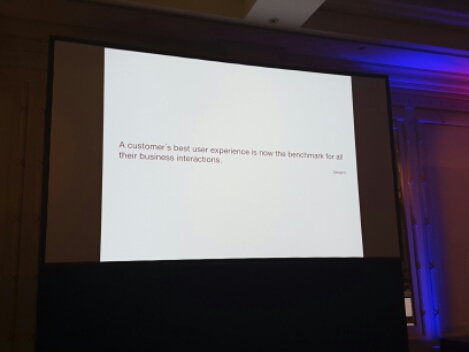

Me: “Let me break it down for you. In good organizations, people can focus on their work and have confidence that if they get their work done, good things will happen for both the company and them personally. It is a true pleasure to work in an organization such as this. Every person can wake up knowing that the work they do will be efficient, effective, and make a difference for the organization and themselves. These things make their jobs both motivating and fulfilling.

“In a poor organization, on the other hand, people spend much of their time fighting organizational boundaries, infighting, and broken processes. They are not even clear on what their jobs are, so there is no way to know if they are getting the job done or not. In the miracle case that they work ridiculous hours and get the job done, they have no idea what it means for the company or their careers. To make it all much worse and rub salt in the wound, when they finally work up the courage to tell management how fucked-up their situation is, management denies there is a problem, then defends the status quo, then ignores the problem.”

Steve: “Okay.”

Me: “Are you aware that your manager Tim has not met with any of his employees in the past six months?”

Steve: “No.”

Me: “Now that you are aware, do you realize that there is no possible way for him to even be informed as to whether or not his organization is good or bad?”

Steve: “Yes.”

Me: “In summary, you and Tim are preventing me from achieving my one and only goal. You have become a barrier blocking me from achieving my most important goal. As a result, if Tim doesn’t meet with each one of his employees in the next twenty-four hours, I will have no choice but to fire him and to fire you. Are we clear?”

Steve: “Crystal.”

It’s rare that a CEO gets the chance to explain in such detail how he feels about something as seemingly insignificant as a regular one-to-one. Admittedly, a lot of organisations aren’t run by such a passionate, driven owner, but that doesn’t make it any less important.

You don’t need to be a CEO of a start-up to benefit from the wisdom in The Hard Thing About Hard Things. Highly recommended.